Editorial |

La dott.ssa Chiara Nepi prepara campioni di typus in cartelle rosse presso la sala 5 dell'Erbario Centrale Italiano a Firenze. Il typus è l'esemplare tramite il quale è stata descritta per la prima volta una specie e viene considerato il rappresentante di riferimento della specie in questione. Nepi è Curatrice delle Collezioni Botaniche presso il Museo di Storia Naturale del Sistema Museale di Ateneo, Università degli Studi di Firenze. Firenze, 13 febbraio 2023.

|

La dott.ssa Chiara Nepi e la dott.ssa Agnese Zeni dialogano nella Sala di Consultazione dell'Erbario Centrale Italiano a Firenze, riflesse nel vetro di uno scaffale contenente campioni di erbari. Nepi è Curatrice delle Collezioni Botaniche presso il Museo di Storia Naturale del Sistema Museale di Ateneo, Università degli Studi di Firenze. Firenze, 13 febbraio 2023.

|

La dott.ssa Chiara Nepi preleva alcuni campioni di erbario di provenienza internazionale conservati negli armadi originali dell'Erbario Centrale Italiano, fondato nel 1842 a Firenze. Nepi è Curatrice delle Collezioni Botaniche presso il Museo di Storia Naturale del Sistema Museale di Ateneo, Università degli Studi di Firenze. Firenze, 13 febbraio 2023.

|

Un campione di erbario presso la Sala di Consultazione dell'Erbario Centrale Italiano a Firenze. Firenze, 13 febbraio 2023.

|

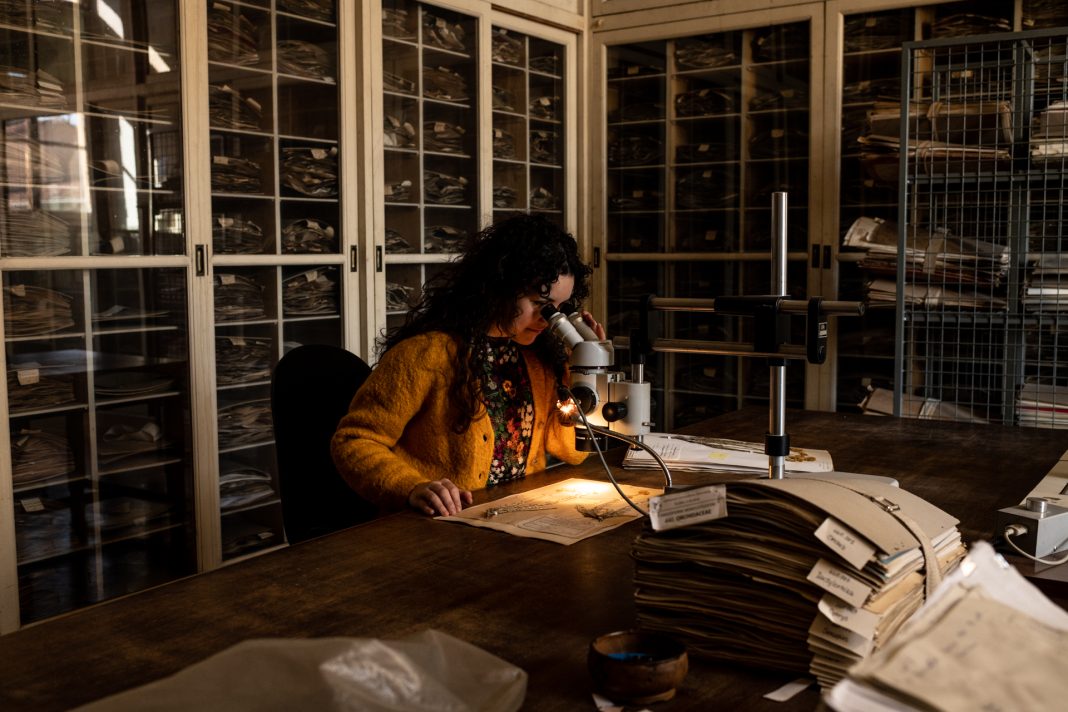

La dott.ssa Agnese Zeni consulta una campione di erbario presso la Sala di Consultazione dell'Erbario Centrale Italiano a Firenze. Zeni è ricercatrice ed esperta di erbari storici presso l'Università degli studi di Parma. Firenze, 13 febbraio 2023.

|

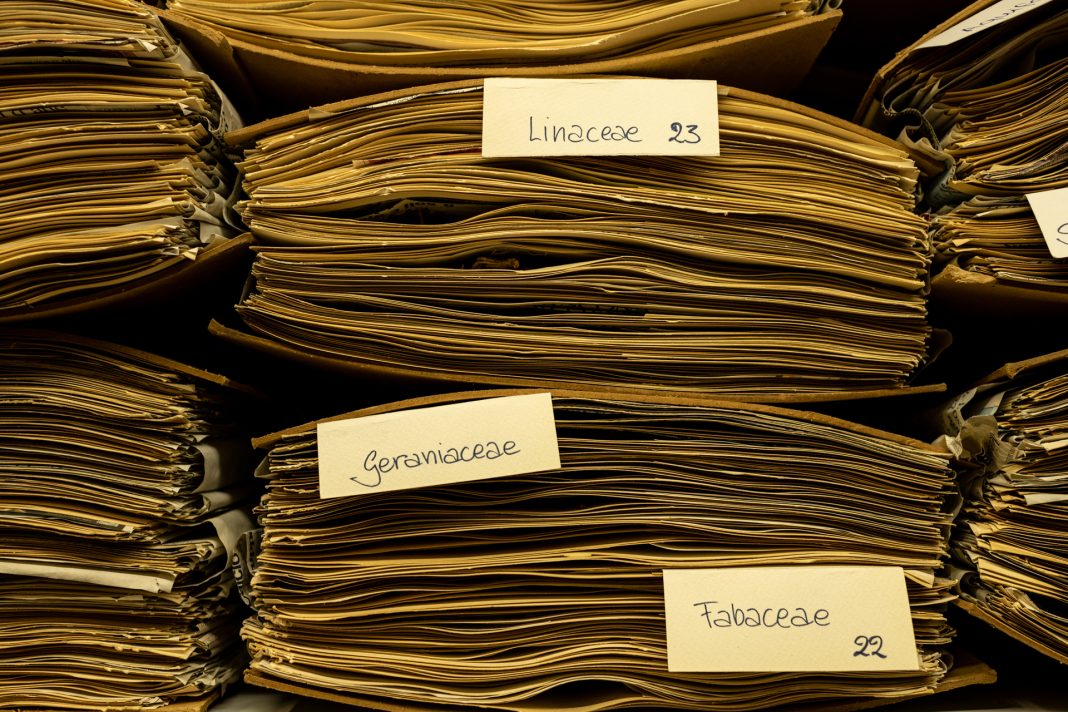

La dott.ssa Chiara Nepi mostra un etichetta per la classificazione dei campioni di erbario dell'Erbario Centrale Italiano, fondato nel 1842 a Firenze. La classificazione dei campioni non è alfabetica ma sistemica, cioè in base alle famiglie di appartenenza. Nepi è Curatrice delle Collezioni Botaniche presso il Museo di Storia Naturale del Sistema Museale di Ateneo, Università degli Studi di Firenze. Firenze, 13 febbraio 2023.

|

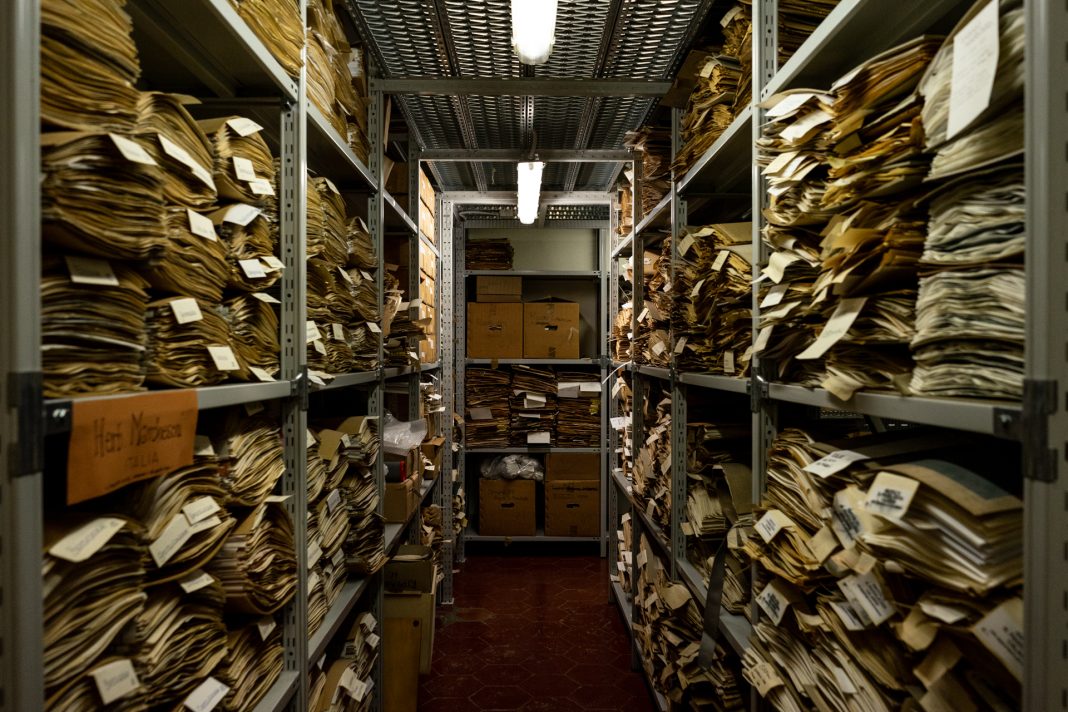

La stanza del Deposito dell'Erbario Centrale Italiano è il luogo dove vengono conservati i campioni di erbario duplici e le collezioni che devono essere ancora studiate. Firenze, 13 febbraio 2023.

|

La stanza del Deposito dell'Erbario Centrale Italiano è il luogo dove vengono conservati i campioni di erbario duplici e le collezioni che devono essere ancora studiate. Firenze, 13 febbraio 2023.

|

Il dott. Lorenzo Cecchi lavora al montaggio di un campione di erbario presso la sala 4 dell'Erbario Centrale Italiano a Firenze. Cecchi è Curatore delle Collezioni Botaniche presso il Museo di Storia Naturale del Sistema Museale di Ateneo, Università degli Studi di Firenze. Firenze, 13 febbraio 2023.

|

La dott.ssa Chiara Nepi mostra un campione di typus della collezione Webb dell'Erbario Centrale Italiano a Firenze. Il typus è l'esemplare tramite il quale è stata descritta per la prima volta una specie e viene considerato il rappresentante di riferimento della specie in questione. Nepi è Curatrice delle Collezioni Botaniche presso il Museo di Storia Naturale del Sistema Museale di Ateneo, Università degli Studi di Firenze. Firenze, 13 febbraio 2023.

|

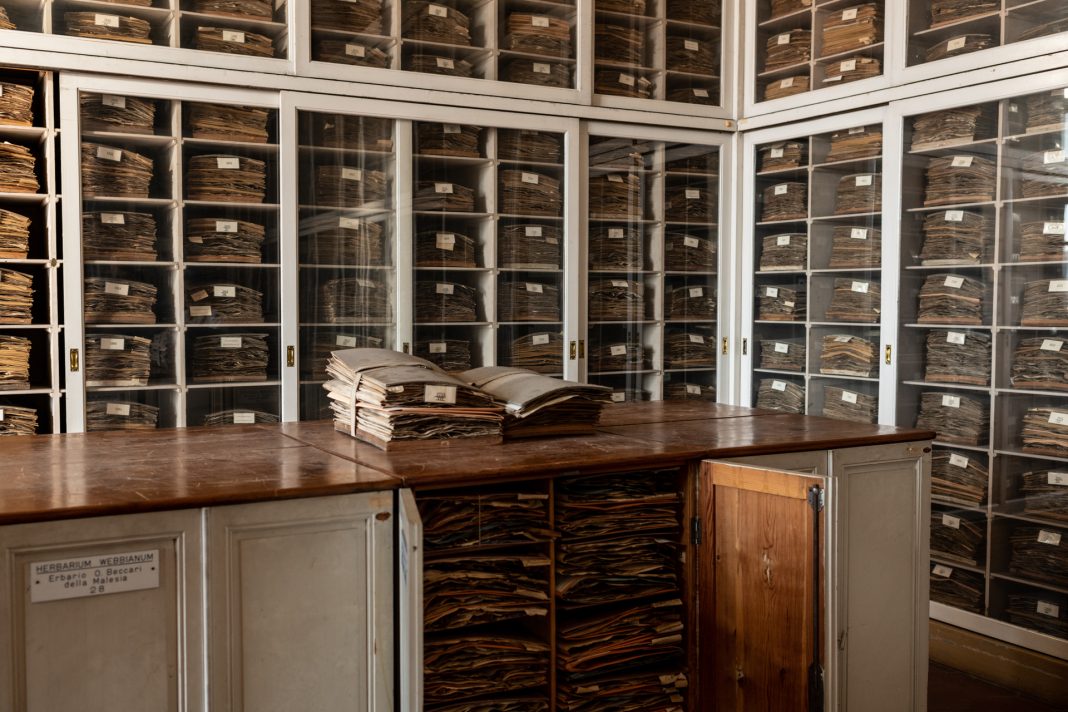

La Sala Webb è una delle sale tematiche dell'Erbario Centrale Italiano a Firenze. L'erbario WebbFirenze, 13 febbraio 2023.

|

Busto di Filippo Parlatore, fondatore dell'Erbario Centrale Italiano a Firenze. Firenze, 13 febbraio 2023.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Two Italian chimney sweeps cheer and wave the Italian flag from the roof of the old Town Hall building, as grand final of the chimney sweeps parade in Santa Maria Maggiore. Elisabetta Zavoli for The New York Times.

|

Chimney sweeps from different countries of the world sit down for a cold beer and a chat outside the restaurant "Il Rusca" in Piazza Risorgimento in Santa Maria Maggiore. Elisabetta Zavoli for The New York Times

|

|

Two young chimeny sweeps from Denmark rest on a bench in the park surrounding Mueso dello Spazzazcamino (Chimney Sweep Museum) in Santa Maria Maggiore. Elisabetta Zavoli for The New York Times

|

Chimney sweeps dance together with tourists in the park surrounding Museo dello Spazzacamino (Chimney Sweep Museum) where a dance floor and a music band have been set in Santa Maria Maggiore. Elisabetta Zavoli for The New York Times.

|

Some chimney sweeps dance in an openair disco set by the festival's organisers in Santa Maria Maggiore town center. Elisabetta Zavoli for The New York

|

Some chimney sweeps hang out in the courtyard of Santa Maria Maggiore Town Hall during the evening party in the town's streets. Elisabetta Zavoli for The New York

|

Some chimney sweeps play traditional music in Piazza Risorgimento in Santa Maria Maggiore, during the evening party in the town's streets. Elisabetta Zavoli for The New York Times.

|

Some chimney sweeps chat in Piazza Risorgimento during the evening party in Santa Maria Maggiore town's streets. Elisabetta Zavoli for The New York Times.

|

Fireworks explode from the roof of Santa Maria Maggiore Town Hall to celebrate the International Reunion of Chimney Sweeps. Elisabetta Zavoli for The New York Times.

|

Chminey sweeps, from different countries of the world, wait the bus to reach Malesco, a town in Val Vigezzo, where they pay tribute to the statue of little Fausto Cappini, who died in Milan at the age of 13 for having touched high tension wires while cleaning a chimney. Elisabetta Zavoli for The New York Times.

|

Dutch chimney sweeps, the only country wearing white working clothes, queue to pay tribute to the statue of little Fausto Cappini, who died in Milan at the age of 13 for having touched high tension wires while cleaning a chimney. The statue is in Malesco, a town of Val Vigezzo. Elisabetta Zavoli for The New York Times.

|

Chimney sweeps from Denmark pay tribute to the statue of little Fausto Cappini, who died in Milan at the age of 13 for having touched high tension wires while cleaning a chimney. The statue is in Malesco, a town of Val Vigezzo. Elisabetta Zavoli for The New York Times.

|

Chimney sweeps from different countries of the world gather in the main square of Villette, a town in Val Vigezzo, before visiting the museum and celebrating a mass dedicated to all the chimey sweeps who died on their working place. Elisabetta Zavoli for The New York Times.

|

Chimney sweeps from Switzerland parade along the narrow pedestrian streets of Villette, a town of Val Vigezzo. Elisabetta Zavoli for The New York Times.

|

Chimney sweeps from Switzerland parade along the narrow pedestrian streets of Villette, a town of Val Vigezzo. Elisabetta Zavoli for The New York Times.

|

Chimney sweeps from different countries gather for a beer and a chat in front of the Town Hall of Villette, Val Vigezzo. Elisabetta Zavoli for The New York Times.

|

Chimney sweeps from Germany wait outside the church of Villette, a town in Val Vigezzo, before attending the mass dedicated to all the chimey sweeps who died on their working place. Elisabetta Zavoli for The New York Times.

|

Some women from Val Vigezzo, wearing traditional clothes, prepare to join the chimney sweeps parade in Santa Maria Maggiore on Sunday morning. Elisabetta Zavoli for The New York Times.

|

Villagers from Val Vigezzo, wearing traditional clothes, dance at the town's music band in a pedestrian street of Santa Maria Maggiore, while waiting to join the chimney sweeps parade on Sunday morning. Elisabetta Zavoli for The New York Times.

|

Policemen gather at the head of the chimney sweeps parade waiting to escort it, while villagers from Val Vigezzo, dressed in traditional clothes, get ready in a pedestrian street of Santa Maria Maggiore. Elisabetta Zavoli for The New York Times.

|

The traditional music band of Val Vigezzo, walks in Piazza Risorgimento, the main square of Santa Maria Maggiore, heading the chimney sweeps parade on Sunday morning. Elisabetta Zavoli for The New York Times.

|

Italian chimney sweeps cheer the crowd in Piazza Risorgimento, in front of the old Town Hall building, to the cry "spazzacamino". Elisabetta Zavoli for The New York Times.

|

The German group of chimney sweeps walks in Piazza Risorgimento, the main square of Santa Maria Maggiore, during the Sunday morning parade. It's a tradition for the chimney sweeps to throw candies and gadgets to the crowd. Elisabetta Zavoli for The New York Times.

|

An Italian chimney sweep stains in soot the face of a woman among the crowd of people come to see the chimney sweeps' parade in Piazza Risorgimento, the main square of Santa Maria Maggiore. Elisabetta Zavoli for The New York Times.

|

An American chimney sweep walks shadowing under a blue umbrella, in Piazza Risorgimento, the main square of Santa Maria Maggiore, during the Sunday morning parade. Elisabetta Zavoli for The New York Times.

|

A group of German chimney sweeps stops in front of the authorities stage in Piazza Risorgimento, in Santa Maria Maggiore, to explode golden heart-shaped confetti. Elisabetta Zavoli for The New York Times.

|

A view of Piazza Risorgimento from Santa Maria Maggiore Town Hall, during the chimney sweeps parade. Elisabetta Zavoli for The New York Times.

|

People come to see the chimney sweeps' parade in Piazza Risorgimento, the main square of Santa Maria Maggiore, arrived since early morning in order to get the best spot. Elisabetta Zavoli for The New York Times.

|

The German group of chimney sweeps walks in Piazza Risorgimento, the main square of Santa Maria Maggiore, during the Sunday morning parade. Elisabetta Zavoli for The New York Times.

|

People cheer and collect the gadgets that chimney sweeps throw to them while parading in Piazza Risorgimento, the main square of Santa Maria Maggiore. Elisabetta Zavoli for The New York Times.

|

The German group of chimney sweeps walks in front of the authorities stage in Piazza Risorgimento, the main square of Santa Maria Maggiore, on Sunday morning. Elisabetta Zavoli for The New York Times.

|

The German group of chimney sweeps walks in Piazza Risorgimento, the main square of Santa Maria Maggiore, during the Sunday morning parade. Elisabetta Zavoli for The New York Times.

|

A Danish chimney sweep walks pushing his red bycicle in front of Museo dello Spazzacamino (Chimney Sweep Museum) in Santa Maria Maggiore. Elisabetta Zavoli for The New York Times

|

Anita Giudice, 21 anni, attivista ambientale e transfeminista presso il Laboratorio sociale di Alessandria (AL), 12 dicembre 2022

|

|

|

|

|

Portraits of Professor David Monacchi, shot for Radar Magazine, Issue#1

https://www.radarmagazine.net/index.php/2020/09/23/il-rumore-dellestinzione/

|

|

A dream of white

"The moment everything closed, I immediately began memorizing texts, poems. It was always something I did in difficult times, even in the past. The first poem was composed by Arsenij Aleksandrovic Tarkovsky about a child who recalls seeing a white nurse from his hospital bed when he became ill. I also thought of the color white during the pandemic: others were enveloped in a white glow."

Isadora Angelini is an award-winning independent actress, dancer and director. She performs at international festivals like Santarcangelo. In 2006, she cofounded Patalò Theatre company with Luca Serrani.

Project Elisabetta Zavoli and Stefania Prandi

Photo by Elisabetta Zavoli @elizavola

Words by Stefania Prandi @stefania.prandi

Setting by Elisabetta Zavoli, Stefania Prandi, Luca Serrani

Styling and Make up by Elisabetta Zavoli and Isadora Angelini

Location ex-Corderia Santarcangelo (RN), Italy

Assistant Luca Serrani @luca_serrani

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Mami Yulie, 56, and her companion Agus, 32, are asleep in their room, in Mami Yuli's house. Jakarta, Indonesia, 2016.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|